1. Michelin goes green

The Royal Lestari Utama (RLU) project in Indonesia – a joint-venture between the French tyre giant Michelin ant its local partner Barito Pacific created in 2014 – is presented in commercial videos as the ultimate success story in green finance. All this with the involvement of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

After an alarming report by the environmental NGO Mighty Earth in 2020, an investigation conducted by Voxeurop over more than a year and a half with our partners from Tempo magazine in Jakarta shows the limits of this operation. In June 2022 Michelin made a full takeover of the RLU joint venture. This led, two months later, to the early redemption of the green bonds issued by French bank BNP Paribas, more than 10 years before their scheduled maturity. Investors therefore no longer have a say in the matter. However, they will surely be interested to know the impact of the operation they helped to finance.

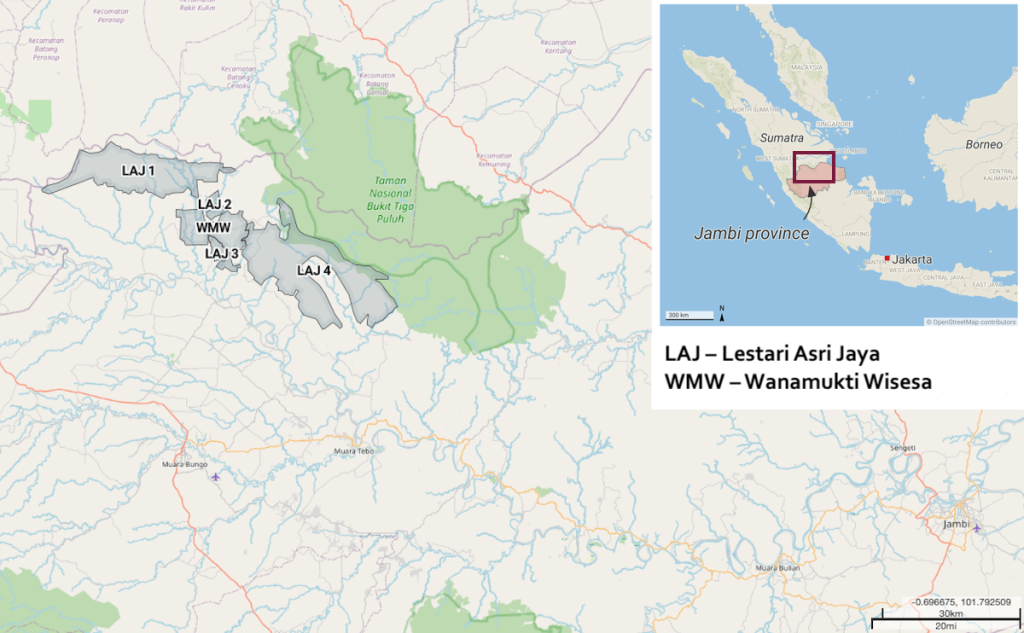

Officially, the story begins on 14 December 2014, when Michelin acquired 49% of Royal Lestari Utama (RLU), an agro-forestry company owned by the Indonesian conglomerate Barito Pacific Group. The latter was founded and led by the wealthy businessman Prajogo Pangestu, dubbed the "Timber King" of Indonesia. According to the Mighty Earth report cited above, the company already had a track record of deforestation, land grabbing, illegal logging and offshore tax evasion using a complex network of companies involved in timber, pulp and palm oil.The joint venture with Barito Pacific, formalised at the beginning of 2015, had the political support of the Indonesian government. It had very grand ambitions: to contribute in a sustainable way to around 10% of Michelin's global supply of natural rubber, by relying on local communities for production and protection of ecosystems. Several sites are involved, in the provinces of Jambi (Sumatra island) and Kalimantan (Borneo island).

To strengthen the credibility of its "green rubber" project, Michelin decided to involve WWF in its venture with Barito Pacific. In March 2015, the two companies signed a no-deforestation commitment: future expansion of RLU's rubber concessions would only be possible on existing farmland, respecting wildlife habitats.

Together, the two shareholders of RLU bet on a 23-year business plan until 2040. They put a combined $100 million of equity (including $55 million from Michelin) into the joint venture's coffers. This was less than necessary to sustain their risky project, given that their forecasted profits were cut by the drop in rubber prices in 2015.

2. A funding-starved project saved by the green-bond gong

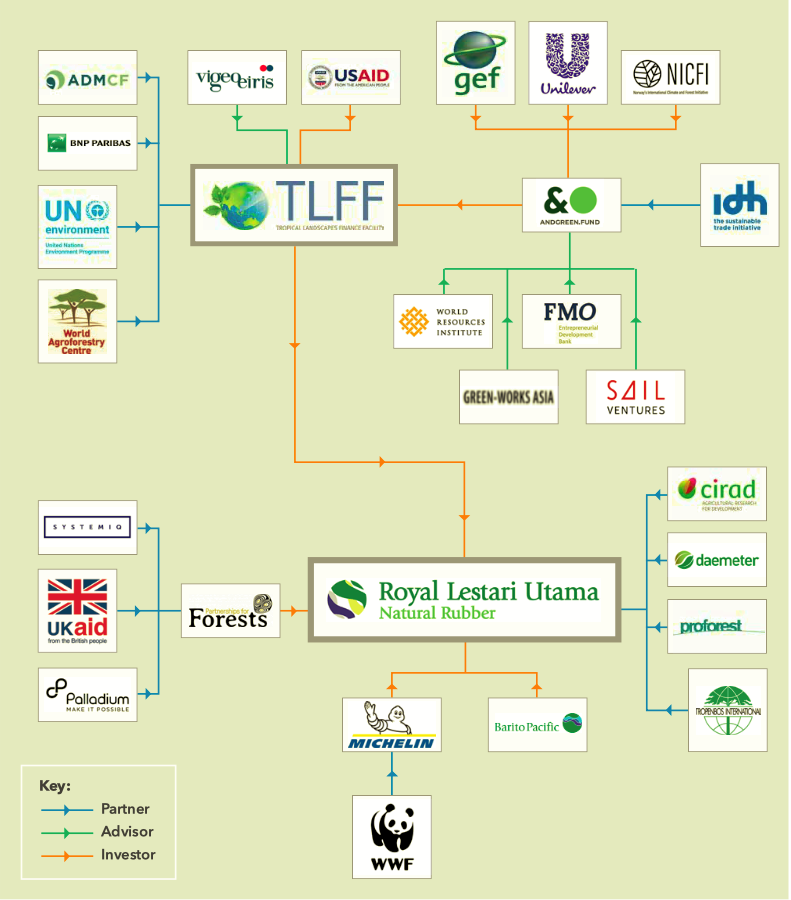

Fortunately for Michelin, in October 2016 a golden opportunity to bail out the joint venture presented itself when BNP Paribas bank co-founded the Tropical Landscape Finance Facility (TLFF) with the support and oversight of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Approved by the Indonesian government and based in the capital Jakarta, TLFF describes itself as an innovative financing platform for commercial ventures related to the Paris Climate Agreement (just signed in 2015, more on that later) and the Sustainable Development Goals.

In November 2016, while BNP Paribas had been looking for an emblematic first project to attract green-minded investors, Michelin and its Indonesian partner Barito Pacific contacted the TLFF. RLU's candidacy came at the right time. For all concerned, it was a golden opportunity.

Following a certification process whose transparency and sincerity raise many questions (see chapter 2), TLFF launched in the spring of 2018 its pilot offering (TLFF I) of $95 million-worth long-dated bonds.

BNP Paribas took over the marketing of the green bonds issued by TLFF, which would use the proceeds of the bonds to provide a loan to RLU. This loan would allow the Indonesian company to invest so as to increase the yields of its plantations, and thus boost financial profitability of the bonds. And BNP Paribas and ADM Capital received a nice commission in the process.

To top it all off, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) guaranteed to cover 50% of the net losses on two-thirds of the TLFF loan amount. It was this guarantee that enabled the A-class bonds (which represent 30% of the total value of the bonds) to obtain the maximum AAA rating.

This landmark deal allowed BNP Paribas to prove that it was a global pioneer in green finance. In December 2017, under the patronage of French president Emmanuel Macron, BNP Paribas and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) partnered to create their Sustainable Finance Facilities (SFF) programme. The aim was to attract $10 billion of private investment by 2025 to support sustainable business projects in developing countries. At the launch ceremony, the TLFF was presented as the kick-off of UNEP's collaboration with BNP Paribas.

Now imagine an environmentally conscious European investor, who drives an electric car with Michelin tyres. They skim over the phrases in the BNP Paribas prospectus (4) that convinced them to buy green bonds: "this once fully forested landscape has suffered severe deforestation in recent years"; "the Borrowers have already planted approximately 18,076 hectares of rubber trees by December 2017"; "[they] plan to generate [...] natural forest areas providing habitat for tigers, elephants, and orangutans" and "carbon sequestration through the development of rubber plantations". The investor’s money is actively fighting climate change, while at the same time holding out the prospect of profit. Win-win.

Alas, that is not the full story. Our investigation reveals that the story did not begin in 2014 with a handshake between Michelin and Barito. It started several years earlier.

3. In Indonesia, deforestation is on the rise

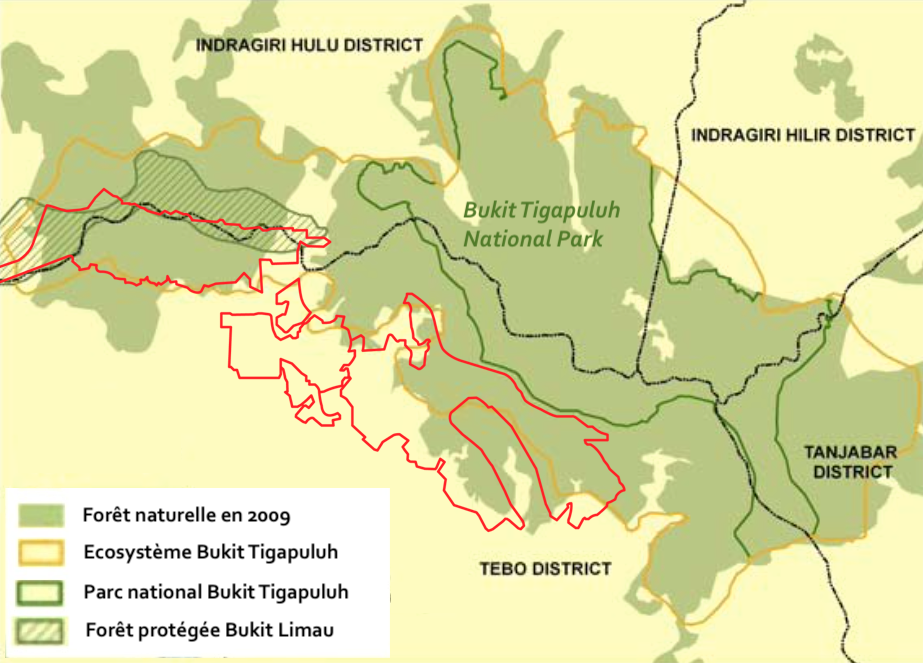

The signing of the joint venture came just a few months after the end of a vast forest clearance operation initiated in 2010 by one of Royal Lestari Utama's subsidiaries, Lestari Asri Jaya (LAJ), at the gateway to the Bukit Tigapuluh national park in Jambi province (on Sumatra). Michelin was already fully aware of this deforestation (see Chapter 2) when it began discussions with Barito Pacific that led to the 2014 agreement.According to Glenn Hurowitz, executive director of the NGO Mighty Earth, the first contact between the two companies took place in mid-2013. This was a few weeks before a first field visit by Michelin officials to Jambi province (on Sumatra Island) in October 2013. These dates, as he told Voxeurop, were confirmed to him by Hélène Paul, Michelin's purchasing manager at the time.

But while the French multinational was conducting field surveys and negotiating its deal with the Indonesian conglomerate, in RLU-owned concessions in Jambi bulldozers belonging to a Barito subsidiary were relentlessly destroying lush vegetation in the Lestari Asri Jaya (LAJ) concession and in the smaller neighbouring Wanamukti Wisesa (WMW) one in order to replace it with rubber trees.

What investors could therefore not know is that a large proportion of the supposedly sustainable rubber plantations - the product of fundraising orchestrated by a UN body and BNP Paribas - grew out of the ashes of native trees cut down by Royal Lestari Utama's subsidiaries in Jambi, prior to the Michelin-Barito Pacific joint-venture.

Contacted by telephone, Hervé Deguine, Michelin's public affairs director, said: "During my first visit to Jambi in March-April 2014, I witnessed massive deforestation largely due to mafia groups [...] who had cornered land on a large scale." However, Deguine added that he had not personally witnessed any deforestation operations specifically by Royal Lestari Utama subsidiaries.

In October-November 2014, a month before launching its joint venture with Barito Pacific, Michelin arranged another site visit. This time the company was accompanied by representatives of WWF and the British environmental consultancy TFT (now transformed into a Swiss-based foundation called Earthworm).

Michelin had commissioned TFT to conduct an audit of Lestari Asri Jaya's (LAJ) operations, which it became aware of in November 2014. TFT/Earthworm provided us a copy of this report, which has not been made public. It shows clearly what Mr Deguine appears not to have seen.

The document includes visual evidence of LAJ's ongoing deforestation of future rubber plantation areas at that time, including photos and geographical coordinates of the machinery involved in clearing forest areas that should have been left intact.

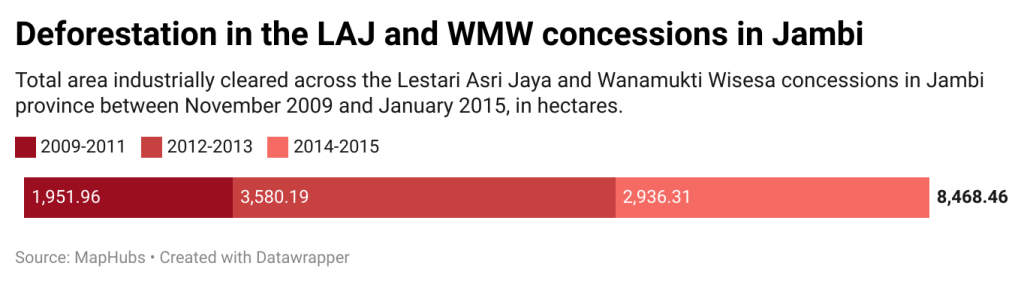

According to the findings of this study, which Michelin did not wish to make public (see Chapter 2) and of which Voxeurop obtained a copy, RLU had deforested about 3,500 hectares of forest in the LAJ concession between 2012 and 2014. And this figure, calculated on the base of LAJ's annual operating plans, is in fact grossly underestimated.

The TLFF is committed to upholding transparency," said Johannes Kieft, secretary-general of the TLFF and senior land-use specialist at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), to Voxeurop. "I was aware of TFT/Earthworm report and of deforestation by Lestari Asri Jaya. The company had the legal obligation to clear logged over forest as it was licensed by the government to use the land for industrial forestry purposes", i.e. rubber production.

A specialist who worked on the case, who also wished to remain anonymous, claimed that BNP Paribas was also aware of RLU’s deforestation. Despite evidence that a very significant proportion of the area covered by the project had been deforested, none of the TLFF stakeholders seems to have objected to Michelin's ecological certification process.

4. Getting a green label: the easy path to a green bond

Obtaining sustainability certification is a purely voluntary process. And it provides access to the magic of the "green" label that helps attract potential investors. All the applicant has to do is hire a qualified auditor from the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) to certify that the application complies with the association's green-bond principles. The reviewer's team examines the application based on documents provided by the applicant (who is also their client) as well as information available online. This is done without necessarily carrying out any on-the-spot checks.

Un rapport de certification est ensuite délivré. Appelé Second Party Opinion ou SPO, il détaille pourquoi le projet présente des avantages conformes aux critères de l’ICMA et mentionne éventuellement toute question portant à controverse méritant d’être divulguée aux investisseurs.

A certification report is then issued. Known as a Second Party Opinion or SPO, it details why the project has benefits that meet ICMA's criteria on paper, but does not in any way guarantee that they actually do. The report should also mention any controversial issues that should be disclosed to investors.

In 2017, TLFF appointed the social and environmental ratings agency Vigeo Eiris as its auditor. The agency gave its green light in January 2018, a few weeks before the bonds were issued. Subsequently, BNP Paribas, which was in charge of marketing the bonds, published a prospectus referring to the Vigeo Eiris bond certification report. To give the investment credibility, TLFF registered both documents on the Singapore Stock Exchange, Southeast Asia's main financial centre.

Conflict of interests

The Vigeo Eiris certification report and the BNP Paribas prospectus are the only two official documents that potential buyers of TLFF green bonds could refer to when deciding whether to invest.

According to information gathered by Voxeurop, Vigeo Eiris conducted interviews with BNP Paribas and Royal Lestari Utama, but not with Michelin. The auditor apparently considered that the Indonesian company was the only entity responsible for business operations.

"Our Second Party Opinions are [...] based on different types of information such as public sources or documents brought to our attention by issuers," said Tim Whatmough, VP of communications for sustainability and ESG (environmental, social and governance) at Moody's, one of the world's largest rating agencies, to Voxeurop. Moody's acquired Vigeo Eiris in 2019.

An auditor's analysis of the issues is based on the information available at the time of the assessment. Ultimately, it is the bond issuer that chooses which items to disclose. Royal Lestari Utama representatives did not share any information regarding deforestation. This would explain why the TFT/Earthworm audit never made it to the offices of Vigeo Eiris. "The report was not ours. It was commissioned by and for Michelin", commented the communications department of RLU to Voxeurop. However, TFT's assessment does appear on the sustainability timeline published by Royal Lestari Utama.

In terms of publicly available information, the only source used by Vigeo Eiris was Factiva, a business intelligence database. Their assessment states that "no ESG issues have been identified within RLU [...] in the last 48 months". However, Vigeo did not seek information on Lestari Asri Jaya.

It should be noted here that Moody's is the rating agency that has assigned the highest rating - AAA - to the Class A bonds issued by the TLFF. This rating is the most coveted by investors. "This is clearly a conflict of interest that casts doubt on the credibility of the voluntary-governance regime for green bonds," said Alex Wijeratna of Mighty Earth to Voxeurop. "We believe that not interviewing Michelin was a serious mistake, given its central role in the joint venture with Royal Lestari Utama since 2014. But the fact that Vigeo Eiris did not verify Lestari Asri Jaya is even more unbelievable, when we know that the prospectus issued by TLFF clearly identifies LAJ as an operating subsidiary of RLU in Jambi."

5. The warnings of NGOs and independent experts

The TFT/Earthworm audit was not the first to sound the alarm on the environmental damage caused by Michelin's future partner. A report by a coalition of NGOs, including the Indonesian branch of WWF, warned in 2010 of the imminent danger to the virgin forest located in a Lestari Asri Jaya concession bordering the Bukit Tigapuluh national park in Sumatra. In November 2015, WWF's local team also co-authored an investigation proving that LAJ was illegally logging in an endagered-species protection area known as Daerah Perlindungan Satwa Liar, as well as outside its concession area. These revelations came months after Michelin and Barito Pacific signed their joint venture and adopted their no-deforestation policy.

8,200 football fields

A better estimate of the extent of the environmental destruction only recently emerged, just before Michelin completed the redemption of the so-called green bonds in August 2022.The latest independent report on the environmental status of the LAJ concession, published by Remark Asia and Daemeter Consulting in May 2022, cites official government data: between 2011 and the end of 2014, the company converted 5,782 hectares of forest into rubber plantations - the equivalent of almost 8,260 football fields.

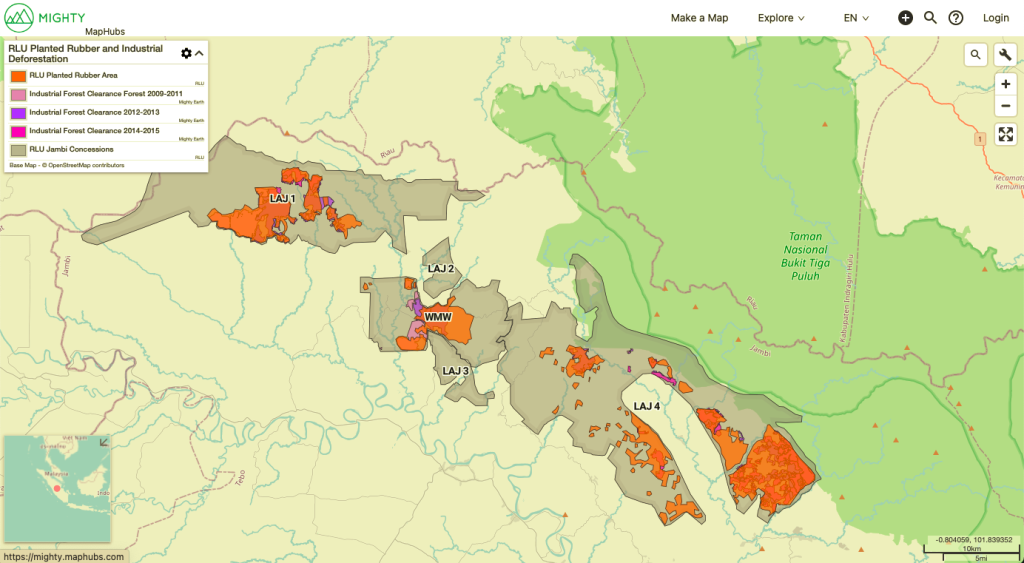

Even this figure seems to be a gross underestimate according to Leo Bottril, CEO of the geospatial technology company Maphubs and the first person to draw public attention to the situation. His satellite calculations were included by the NGO Mighty Earth in its October 2020 report (and again in the 2021 one).

Recently, Bottril shared with Voxeurop an updated map. It shows that an estimated total of 8,468.46 hectares had been deforested within the LAJ and WMW concessions in Jambi prior to the 2015 joint venture. (To date, rubber plantations have not yet covered all of the deforested area).

The conclusion that can be drawn from averaging the two different figures provided by the government and Bottril is that about one third of the rubber plantations financed by the green bonds are located in the area that was deforested in Jambi province before the joint venture between Michelin and Barito Pacific was signed in December 2014.

Indeed, according to RLU's 2020 sustainability report, the green bonds financed the first 19,000 hectares of rubber trees planted by RLU since 2008 and before Michelin became a shareholder, in December 2014. These were mostly located in the province of Jambi, Sumatra, and to a lesser extent in Borneo.

6. Violation of green bond criteria

The fact that RLU used a loan financed by green bonds to plant rubber trees on the site of a newly deforested tropical forest raises many questions. Moreover, RLU used one third of the borrowed money to repay earlier bank loans, which had financed rubber plantations prior to Michelin's involvement. This is confirmed by the BNP Paribas prospectus and other documents examined by Voxeurop.

"Essentially, it appears that a significant portion of the $95 million TLFF loan was used to cover expenses incurred by Royal Lestari Utama to deforest and plant rubber trees in a globally important wilderness area," says Alex Wijeratna, of Mighty Earth in response to the Voxeurop revelations. "It is safe to conclude that green bondholders have unwittingly rewarded environmental destruction with about a third of their $-95 million investment."

None of this is necessarily illegal. In 2010, RLU received a government permit to plant timber and rubber trees for up to 60 years based on an environmental impact assessment from 2009. Officially, the investors thus had an unquestionable right to receive income from the sale of rubber, including from rubber trees grown in an industrially deforested area that was previously home to elephants, orangutans and tigers. All three animals are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of threatened species. In particular, according to a study of the area's elephants by German biologist Alex Moßbrucke, former director of the International Elephant Project. "the probability of extinction over a 500-year period is estimated at 100%", despite RLU's commitments to habitat protection.

Yet, "what investor would want to invest in a 'green project' that has deliberately eradicated a pristine rainforest inhabited by indigenous people and home to three iconic species, all while releasing huge carbon emissions that contribute to climate change?" laments Alex Wijeratna of Mighty Earth.

Furthermore, it was the green "visa" granted in January 2018 by Vigeo Eiris that made it possible to register the TLFF bonds in the database of the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the global fundraising platform that directs private capital to projects that help reduce carbon emissions. Vigeo Eiris is indeed an auditor also approved by the CBI. The accreditation of the bonds in CBI's climate-friendly investment showcase has contributed to their reputation and visibility to potential investors.

Land conversion and deforestation, and the spirit of green bonds

Relying on the flawed Vigeo Eiris assessment (see Chapter 2), CBI endorsed the TLFF's obligations without taking into account the greenhouse gasses released by past deforestation. CBI could not have been aware of this, given that RLU and BNP had failed to report it to Vigeo Eiris.

Bottrill calculated that deforestation in the LAJ concession will contribute to the release of approximately 13 million tonnes of CO2 between 2009 (the year before deforestation began in the LAJ concession) and 2030. This amount is not offset by the 8.27 million tonnes that RLU estimates will be absorbed by partial reforestation and rubber plantations between 2014 (the year of the agreement between Michelin and Barito) and 2030. As a result, RLU's operations will lead to an overall net increase in carbon emissions, rather than a reduction as requested by CBI.

In a letter to the Climate Bonds Initiative in March 2021, Mighty Earth asked it to remove the TLFF bonds from its database. The environmental NGO argued that "this failure to disclose [...] the known key information that the subsidiary of Michelin's local partner [...] was one of the major causes of the land clearing and deforestation on its concessions in Jambi [...] constitutes an extremely serious - and ultimately misleading - omission and [...] a gross violation of Green and Sustainability Bond principles" established by ICMA. These require transparent disclosure of the environmental risks associated with funded projects.

According to an ICMA expert on sustainable finance who wished to remain anonymous, "it should be clear that land conversion and deforestation are not in the spirit of green bonds, even assuming that the final [outcome] is green, as in the case of sustainable agriculture for example. External auditors and investors would doubtless not endorse this [as] their reputation could suffer."

Paul Vermaak, director of standards at CBI, told Voxeurop: "Our database can accept bonds that support the sustainable transition of agribusinesses with a history of land conversion – i.e. it must have taken place long before – but not those that might support companies that have cleared the forest just before publishing a 'no-deforestation policy'. This would be a manipulation of the system to unfairly extract money from investors. It would be up to ICMA's qualified reviewers to avoid such an unintended consequence."

To hide the clearcutting that preceded the joint venture between Michelin and Barito Pacific could thus reasonably be described as a breach of the green-bond guidelines set out by the International Capital Market Association and the CBI. It also compromised RLU's adherence to the Environmental and Social Sustainability Performance Standards of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private investment arm of the World Bank.

Indeed, the environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria mentioned in the green-bond prospectus proclaim full compliance with the ICMA principles as well as with the IFC standards. Royal Lestari Utama should therefore have been subject to the same environmental and social requirements as those for companies applying for IFC funding. In its Second Party Opinion – a form of audit – Vigeo Eiris made it clear that the environmental benefits of the project "are conditional on the implementation of the [...] IFC performance standards".

Among these, the chapter on conservation blacklists projects that result in a net loss of biodiversity – a concept that includes any natural forest that represents an important habitat for threatened species or for indigenous communities.

Environmental trickery

Without referring specifically to RLU, the IFC press office suggested that its venture might well fall under this non-compliance clause. In an email exchange with Voxeurop, it said that "the implementation of the national legal framework" and "the company's non-deforestation policy do not come into play [...], i.e. it does not matter whether or not the company had such a policy or a clearing permit (where it has degraded the habitat), it still has to prove [...] that its project resulted in no net loss (of biodiversity) [...]" to comply with the IFC standards.

In particular, the IFC considers that companies are liable for any biodiversity loss they cause by deliberately degrading a natural habitat "in anticipation of obtaining financing from a lender [...] for the project".

Indeed, according to both the green-bond prospectus and the latest independent report on environmental protection in the LAJ concession, published in May 2022 by Remark Asia and Daemeter Consulting, rubber planting in fact exploded between early 2013 – when Michelin first visited the site – and late 2014, when the joint venture was signed.

"The Michelin-Barito Pacific joint venture had planned from the start to seek new financing," a source familiar with the RLU project told Voxeurop on condition of anonymity. "But the banks did not consider the rubber plantations to be assets sufficient to constitute a mortgage guarantee, as the joint venture had hoped. And that was because the land is owned by the government, and the government's licence to RLU is time-limited."

According to Alex Wijeratna of Mighty Earth, "All of this is evidence enough that the conversion of the forest to rubber plantations was accelerating in anticipation of the deal that Michelin and Barito Pacific had been negotiating for months. It seems that their intention was precisely to maximise the plantation area in order to secure financing for their project, which in reality had begun long before the joint venture and RLU's declaration of non-deforestation."

The prospectus of the green-bond offering marketed by BNP Paribas confirms that total production includes rubber trees planted before 2015. These account for more than half of the area converted at the time of the bond issue.

Wijeratna concludes: "It is reasonable to say that these green bonds are the result of a long-planned quest for funding. Habitat destruction is being pushed forward with the complicity of Michelin."

"From 2014, during our successive field visits, we observed areas that had been deforested and planted with rubber trees, even though they were unsuitable for rubber farming. Conversely, other areas, more suitable, were not being exploited," confirmed Hervé Deguine, Michelin's public affairs director, to Voxeurop. He implicitly questions The reliability of the environmental impact assessment approved by the Jakarta government in 2009, which would have allowed Lestari Asri Jaya to destroy valuable but degraded ecosystems, is implicitly questioned even by Michelin's public affairs director. "We found a valuable forest where [according to LAJ's logging plan] there should only be bushes to clear. We had to change the plans to protect these places," Hervé Deguine told Voxeurop, referring to the period following the signing of the joint venture with Barito Pacific, before which Michelin could only passively watch the industrial deforestation.

In a response published a few weeks after a Mighty Earth report revealed the extent of deforestation carried out by its subsidiary Lestari Asri Jaya in its Jambi concession, RLU explained that industrial deforestation prior to the signing of the joint venture was only in areas "already considered degraded, logged or shrub land at the time these licences were initially granted".

Such statements may give the false impression that before RLU's intervention, the habitat was already so degraded that clearcutting did not result in substantial biodiversity loss.

However, the International Finance Corporation is clear that "human-induced habitat modification is [...] not necessarily an indicator of its biodiversity value" and "if, in the opinion of a competent professional, the habitat still contains [...] one or more native ecosystems, it should be considered a natural habitat, regardless of its degree of degradation."

Indeed, environmental experts and documents consulted by Voxeurop confirmed that the area cleared by RLU’s subsidiary Lestari Asri Jaya was still an integral part of the forest habitat of Bukit Tigapuluh National Park, which the Indonesian government itself had deemed vital for endangered species.

In 2009 an implementation plan, developed by the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS), was agreed by NGOs (such as WWF) and local governments. It was also officially approved by the Directorate General for Natural Resources and Ecosystem Conservation of Indonesia’s environment ministry. However, despite its commitments, even at the international level, the Indonesian government gave in to economic interests. The area that should have been called "Bukit Tigapuluh Ecosystem" never saw the light of day and was instead largely left to the clearcutters such as LAJ.

7. Michelin ends the game

In February 2022, TLFF, the green financing platform of the United Nations and BNP Paribas, itself requested repayment of the loan, citing RLU’s failure to meet the annual interest payment deadline. TLFF persuaded the bondholders to accept Michelin's proposal for early repayment (the maturity date was February 2033).

"Michelin initially went for the green bonds despite the rather high interest rate, because it had no interest in investing more of its own money in a company it did not control," notes a well-informed source. This remark underlines the fundamentally commercial nature of this eco-finance operation. "After taking full control of RLU, Michelin found it more convenient to repay the loan and then borrow at lower rates in the market."

But investors who helped with the venture can rest assured that "as part of the purchase of Barito Pacific's shares in Royal Lestari Utama, the Michelin Group has committed to continuing to meet RLU's environmental and social objectives over the long term, beyond the repayment of the TLFF bonds," according to the official statement.

The project's achievements are assessed annually, based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to which RLU has signed up, including those stipulated in the TLFF guidelines. Compliance with these criteria is entirely voluntary and cannot be enforced by public authorities, as our investigation shows. The prospectus accompanying the green bonds also states that the ESG principles mentioned "are not [...] legally binding on the issuer or any other party (including RLU, currently a subsidiary of Michelin)".

The weakness of the commitments made through the bond issue is now all the more obvious given that the investors, having been reimbursed for their outlay, are out of the picture. "The less outside investment there is in a project, the less transparent it will be and the less say stakeholders will have in its progress," a lawyer specialising in business law told Voxeurop. "I don't know if this is what motivated Michelin to buy back the green bonds, but the consequence is that these bondholders will be very unlikely to pressure the company to live up to what it originally announced."

In other words, Michelin has no obligation to generate social and environmental benefits in return for the funding obtained through the bonds.

WWF's withdrawal from the project in March 2020 does not point to a happy - green - outcome. "We have concerns about their commitment to conservation and their lack of transparency," said a WWF spokesperson in explaining the decision to walk away from Michelin. "All our concerns have been passed on to the highest authorities at Royal Lestari and Michelin so that they may act accordingly."

The fieldwork in Indonesia carried out by our media partner Tempo was supported by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. The investigation was also supported by the Environmental Reporting Collective, Journalismfund Europe, the GRID-Arendal Investigative Environmental Journalism Grants programme, and Mediabridge.

With the support of Investigative Journalism for Europe

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!